NO

BORDERS

“Hero”

Film

Review by John Demetry

Reality exists. Metaphors express emotions.

Shared recognition of the beautiful – and, ultimately, the sublime – unite a

community. Zhang Yimou’s “Hero” daringly proposes that faith in these eternal

truths should be the basis for social organization, intimate interaction, and

humane Pop-Art (each indivisible from the other). Perhaps still reeling from a

symbol’s destruction (9/11), some in New York City dismiss Zhang’s profound

assertion by labeling it: “fascinatin’ Fascism.” Zhang, in fact, makes

undeniable the foundation for democratic vision (so that the film’s haters

suffer the same anxiety of freedom exposed in Jonathan Demme’s 2004 film of

“The Manchurian Candidate”).

Those who would deny Zhang’s revelation perform

the true Fascist act: a repressive annihilation – then manipulation – of

meaning. Zhang, reinterpreting the mythic birth of his nation, dramatizes

liberating imagination when the Emperor of Qin (Daoming Chen) contemplates a

scroll bearing the “twentieth variation” of the sign for the word “sword” –  the artform of the subjugated Zhao

tribe. Before that symbol, Qin announces his history-changing realization about

the warrior’s ultimate ideal, understood in the nuances of form in the

calligraphic artwork: “The sword disappears. The warrior embraces all around

him. Only peace remains.”

the artform of the subjugated Zhao

tribe. Before that symbol, Qin announces his history-changing realization about

the warrior’s ultimate ideal, understood in the nuances of form in the

calligraphic artwork: “The sword disappears. The warrior embraces all around

him. Only peace remains.”

Zhang invites the viewer to “read” his complex

film with the same sense of responsibility and awe that the King expresses. It

is the best film released in the United States this year. To reject that

achievement as Fascist is to wilfully misunderstand how profoundly “Hero”

elucidates History, the process by which civilization evolves to respond to spiritual

need. “Hero” dramatizes the move from tribal warfare to monarchical

unification. Doing so, “Hero” joins John Boorman’s similarly towering

post-postmodern work of ecstatic philology “Excalibur” (the secret of the

scroll reflects the secret of the Holy Grail) and the establishment of justice

(catharsis) after generations of revenge/bloodlust in Aeschylus’ Greek Tragedy

“The Oresteia” (mirrored in this film’s Fritz-Lang-inspired chorus with its

insistence on the Word of the Law). The process proves violent – “dialectical”

– but it also evidences the historical resonance and complex signification of

cultural totems.

As in the great American films of the year –

Steven Spielberg’s “The Terminal” and Demme’s “The Manchurian Candidate” – both

of which recognized the American experience as encapsulated by Black-American

expression, the sign of a conquered people in “Hero” shapes the future of the

new nation. In “The Terminal”, this truth was found in jazz’s global

inspiration. “The Manchurian Candidate” identified this veracity in the

gestures of compassion shared by people suffering from oppression’s duress –

first, between Blacks, then, proving democracy’s hope, cross-racially.

Now, “Hero” validates the faith expressed by

the calligraphy school – soon to be wiped out by the arrows of the Qin

Emperor’s mighty army: “They can never eliminate our written word. Today, we

learn the true meaning of our art.” That written word – the true meaning of the

art – will define the new nation, as the sword of war phases into the symbol of

unification. Conversely, Fascism means to erase history and to cleanse

multi-ethnic influence – much like the Western critics denying “Hero”. They

would prefer that China never existed. Fascists, heal thyself!

Zhang’s retelling of the legend imposes a great

responsibility on the spectator. “Historical inaccuracy?” – a specious argument

when dealing with myth. In “Hero”, Truth is History. The multiple narratives

that make up the film reveal the ideals and motivations of storytellers, the

spiritual struggle – the kernel of truth – around which a new nation will form.

As Spielberg and Demme reiterate: for freedom to exist, responsibility must be

embraced. The beauty of “Hero” (diminished by some as merely “pretty” – an

anti-democratic conceit) makes the embrace both challenging and undeniable, an

empathic gambit and gesture. China’s destiny becomes the spectator’s own: “Our

Land.” (John Ford must smile down from Heaven at this film’s yellow ribbon.)

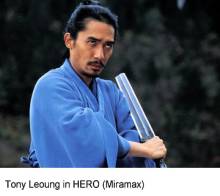

“Beautiful calligraphy,” Nameless (Jet Li)

compliments Broken Sword (Tony Leung) on the creation of the “sword” scroll.

Nameless deflected the Emperor’s “storm” of arrows from disturbing Broken

Sword’s creation of the scroll. That sequence locates graphic similarity between

Nameless and Flying Snow’s (Maggie Cheung) bounding whirls through the air and

Broken Sword’s calligraphy and swaying hair: a dance of liberation and shared

sensitivity amidst the hegemonic onslaught of arrows. “Beautiful swordplay,”

Broken Sword returns the favor: “Without your sword, the scroll would not

exist.” Zhang writes the Truth essential to each of the narratives, and to the

story proper, in the film’s mise-en-scene. Every movement in space inscribes

meaning to be read: feelings and thoughts made concrete, legible.

This is dramatized in the first

fight sequence between Nameless and chess- and music-lover Sky (Donnie Yen), a

Zhao assassin, like Broken Sword and Flying Snow whose existence endangers the

Emperor. After detailing the space of the chess grounds where the actors engage

in conflict, Zhang presents the warriors’ battle as it occurs in their minds.

Cinematographer Christopher Doyle switches stocks from color to

black-and-white, a PoMo activation of consciousness that pays off in the intense

color schemes of the following narratives. Thus, Doyle represents the

characters’ shared visualization. “Combat unfolded in the depths of our minds”

– a process Catholic thinkers refer to as evidence of faith.

This is dramatized in the first

fight sequence between Nameless and chess- and music-lover Sky (Donnie Yen), a

Zhao assassin, like Broken Sword and Flying Snow whose existence endangers the

Emperor. After detailing the space of the chess grounds where the actors engage

in conflict, Zhang presents the warriors’ battle as it occurs in their minds.

Cinematographer Christopher Doyle switches stocks from color to

black-and-white, a PoMo activation of consciousness that pays off in the intense

color schemes of the following narratives. Thus, Doyle represents the

characters’ shared visualization. “Combat unfolded in the depths of our minds”

– a process Catholic thinkers refer to as evidence of faith.

A dazzling, gravity-defying dance ensues between

the opponents (one protecting the Emperor, one intent on killing him). It is

politics – converging motivations – in motion. The sequence is instigated – and

concluded – by the performance of a string musician. Nameless pays the musician

to play. A neat shot of coins falling into a bowl is followed by a comic

ellipsis to a shot of the musician’s preparations – a concise negotiation of

folk culture’s transformation to global pop culture (e.g. the international

appeal of Kung Fu movie codes). When the strings on the instrument break,

Nameless exacts the mortal blow, signifying a choice – an act of freedom and

sacrifice – that distinguishes from what might have been. “How swift your sword

must be,” the Emperor punctuates Nameless’ tale.

Through the mirroring, contradictory

narratives, Zhang utilizes contemporary sophistication – deconstructionist

modes of discourse – to get to spiritual essences: the epitome of

post-postmodern art. The candle flames separating Nameless and the Emperor sway

in response to Nameless’ “murderous intent” and encourage the Emperor to

analyze with skepticism Nameless’ story of the infidelity that divides and

defeats lovers Broken Sword and Flying Snow. This story reveals its own truths

to be read: Emotional conflicts wrought out in the winding corridors and

peek-a-bamboo walls of the calligraphy school. Emotional boundaries edged with

mortal danger, a sword pierces the wall and the first of the film’s three drops

of blood is spilled: “We are both very foolish,” Broken Sword bemoans his fate

to Flying Snow.

The essential emotions in this section expand

into the revelations presented later in the film. The need for a home conflicts

with unresolved pain, dividing lovers and comrades, subjects and rulers. Each

of the main characters – Nameless, Broken Sword, Snow, and Moon (Zhang Zhiyi) –

are orphans of the storm. A potential nation – the home for which each

character longs – hangs in the sway of unexpressed emotions. Broken Sword

sacrifices his life to prove the connection between his faith in “Our Land” and

his love for – his desire to assuage the pain of – Snow, who has inherited her

father’s sword as an oath of vengeance (there’s a reason he’s named Broken

Sword). When Moon, Broken Sword’s pupil, despairs over the loss of her adopted

family, Zhang Yimou answers her need (through montage) with Nameless’ final,

heroic offering (similar to the queered radical sensitivity in Mel Gibson’s

“The Passion of the Christ”, in which Jesus reinvents the family/community,

assigning the Apostle John as the new son of His mother amidst the anguish on

the cross – intuiting the connection, critics show no faith).

Just as Nameless characteristically

colors his story with sorrow and vengeance, the Emperor retells the story in

the image of his own idealism. He envisions the deaths of Broken Sword and Snow

as sacrifices to their cause. Their faith in Nameless’ swift sword is

consecrated by Moon’s gesture of hope and look of trust (giving Nameless the

sword of her master to present to the Emperor). The assassins’ common idealism

is staged via the Emperor’s own dream. Nameless proves his prowess by breaking

the bundles of scrolls and toppling the school’s library (dissolving a “fasc” –

the root of the word “Fascism”). Zhang Yimou cross-cuts the meeting of Broken

Sword and Snow as they pass through blue veils (“No borders”) to consummate

their sacrifice: “To go is to die.” In this sequence, the Emperor establishes

the values of idealism, nation, and brotherhood as an alternative to (a means

to address) the – recognizably, palpably expressed – uncontainable anguish

portrayed in Nameless’ initial version of the story.

Just as Nameless characteristically

colors his story with sorrow and vengeance, the Emperor retells the story in

the image of his own idealism. He envisions the deaths of Broken Sword and Snow

as sacrifices to their cause. Their faith in Nameless’ swift sword is

consecrated by Moon’s gesture of hope and look of trust (giving Nameless the

sword of her master to present to the Emperor). The assassins’ common idealism

is staged via the Emperor’s own dream. Nameless proves his prowess by breaking

the bundles of scrolls and toppling the school’s library (dissolving a “fasc” –

the root of the word “Fascism”). Zhang Yimou cross-cuts the meeting of Broken

Sword and Snow as they pass through blue veils (“No borders”) to consummate

their sacrifice: “To go is to die.” In this sequence, the Emperor establishes

the values of idealism, nation, and brotherhood as an alternative to (a means

to address) the – recognizably, palpably expressed – uncontainable anguish

portrayed in Nameless’ initial version of the story.

What the Emperor learns, however, is that

Broken Sword had already “read” the Emperor’s great intentions: “Who would have

thought an assassin would understand me best?” Understanding the connection

between calligraphy (expression) and swordplay (political force), Broken Sword

deciphers the Emperor’s tactical brilliance as a declaration of faith. During

their fateful duel, the Emperor scribes his ideal in space: cutting down the

green tapestries that adorn his great hall. As Broken Sword spares the

Emperor’s life (blood-drop number three), the tapestries plummet to the ground.

Through the sharing and, in response, analyzing

of each of their stories, Nameless (“I have no family name,” he narrates at the

beginning) and the Emperor achieve a similar understanding: the shared

sensitivity, recognition of symbols and offering of gestures through which the

Emperor will realize his destiny and address the spiritual need of the film’s

marginalized heroes. Their interaction outlines the very basis of culture, from

the sword to the embrace.

This connection takes the characters and

spectators beyond language to a land with “No borders.” Of all the beautiful

images (each shot is sublime), none are more beautiful than the close-ups of

Maggie Cheung’s face as Flying Snow: spying on her lover’s infidelity (a slice

of light illuminating her eyes and tracing the tracks of her tears), facing the

challenge of Moon’s revenge (pale make-up revealing lines of experience), the

unbridled facial transformation of her final scream (Maggie Cheung, YOU are the

quarry!). Tony Leung, whose enlightened, sexy concentration gives way to

overwhelming feelings, and Zhang Zhiyi, whose every emphatic gesture conveys

emotions as if they were new-born, match Maggie Cheung’s majesty. Between the

three of them, no human emotion goes unexpressed.

When Flying Snow and Moon fight, Moon’s death

transforms the falling leaves (which Zhang Yimou graphically matches to Flying

Snow’s tearful response to the death of Broken Sword) from gold to red – as if

colored by the single drop of blood (number 2) from Flying Snow’s sword. Zhang

Yimou associates the color-coding of each of the stories (red, blue, green,

white) with the phenomenon of emotion: the release storyteller Nameless so

desperately desires. With its uniqueness and shadings, its inability to be

contained by context, the experiences of color and emotions are equally

sublime. The shared recognition of the sublime (the characters’ revelatory

gestures, the film spectators’ imaginative feeling) define the film’s

contemporary vision of social possibility.

As the Emperor informs us in his

narration of his version of the Broken Sword/Flying Snow drama, Nameless and

Broken sword fight each other with their hearts (just as Nameless and Sky

fought with their minds). Nameless and Broken Sword dance, glide, skip, and

hover above a reflecting lake, soaring on the wings of their feelings. The site

of Snow’s funeral pyre also symbolizes Broken Sword and Snow’s dream of home, a

land with “No borders” (a spiritual conception made concrete in “Our Land”).

Broken Sword and Nameless’ faces are super-imposed over longshots of the

landscape (pace “Excalibur”: “The Land and the King are one”).

As the Emperor informs us in his

narration of his version of the Broken Sword/Flying Snow drama, Nameless and

Broken sword fight each other with their hearts (just as Nameless and Sky

fought with their minds). Nameless and Broken Sword dance, glide, skip, and

hover above a reflecting lake, soaring on the wings of their feelings. The site

of Snow’s funeral pyre also symbolizes Broken Sword and Snow’s dream of home, a

land with “No borders” (a spiritual conception made concrete in “Our Land”).

Broken Sword and Nameless’ faces are super-imposed over longshots of the

landscape (pace “Excalibur”: “The Land and the King are one”).

Nameless and Broken Sword’s engagement of each

other through choreography/swordplay signify their sense of brotherhood as well

as the gravity of the loss inevitable in their plan to assassinate the Emperor.

No greater elegiac image exists in the history of cinema than the underwater

p.o.v. of Broken Sword and Nameless in combat just above the lake. It’s ballet!

It’s opera!! It’s jazz!!! The two, in an improvised moment of bonding, bat a

drop of water to each other with their swords. The water drop swerves through

the air and lands on the face of the dead Snow, representing a teardrop.

Distracting Broken Sword, it opens him to attack from Nameless. The vision of

this symbolic teardrop, however, forces Nameless against the surface of the

water. The water splashes onto his face as if he were weeping, signifying his

depth of feeling. He turns his back to the lover’s last goodbye.

No borders. Emotions are miracles. You can walk

on water.